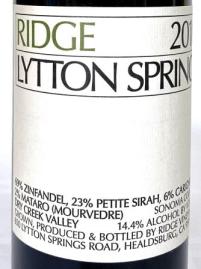

No, I am not boosting my by-now antique book – just the concept behind it: The right wine – the wine that really fits the occasion and meshes with the food – can elevate any meal to a memorable experience. Grilled chopped sirloin and an eight-year-old Ridge Zinfandel aren’t just fuel, and they’re miles beyond a burger and a beer: They’re Dinner.

.

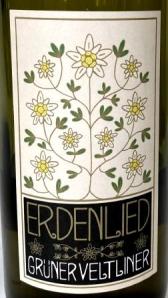

You don’t even have to go as lofty as Ridge. For our traditional St. Patrick’s Day dinner of corned beef and cabbage, I opened a two-year-old, very inexpensive bottle of Gruner Veltliner, from a producer I knew nothing of. It was what I had on hand. That bottle of what might have been just plonk made a fascinating and utterly pleasing companion to the spicing of the corned beef and the sweetness of a Savoy cabbage. We couldn’t have had a more enjoyable meal with a much more prestigious meat or wine than that great match gave us.

.

And that’s the point: The mesh of the food and the wine doesn’t depend on the rarity or reputation or prestige of either. It depends only on those simple miracles that can happen in your mouth every day.

Yes, you need to know something to make that miracle happen. You need to know your own likes and dislikes. You need to have at least a rudimentary idea of what the food you’re about to eat tastes like: You can’t match a wine with a dish you don’t know. And you need to know at least the general character of the kind of wine you’re considering, if not the specifics of any producer’s bottlings.

That’s why sommeliers are useful: They know their restaurant’s food, and they know its cellar, far better than you could. For your home cooking, you’re the sommelier. You know your cooking, and you know your bottle: All you have to do is pay attention, think about the meal for a minute or two, letting your own experience of the food and/or your wine guide you. There is no mystery. The only equipment you need is taste buds.

.

Some examples: With a plainly grilled or broiled red meat, any number of inexpensive young red wines will match quite nicely. If you want a soft wine, a negociant’s basic Burgundy or a Dolcetto will work well. If you want something with some acidity, Côtes du Rhône or Barbera, Beaujolais Villages or Lacryma Christi will provide it.

.

This is not to say that the matter can’t be made complex: Dining at Taillevent on its ris de veau en croûte and trying to choose a wine from its intimidating wine list (Where was the comma in that price?) is complex indeed and, if your bank account can stand it, thrilling, but that isn’t simple food or everyday wine.

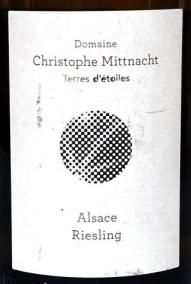

For a different sort of example of what I mean: A fresh filet of flounder, salted, peppered, lightly floured, and quickly sauteed in butter is going to be lovely with a young, unoaked Chardonnay – or Fiano, or Riesling, or dry Chenin Blanc, or even Muscadet. Any young, dry, unoaked, not-too-assertive white wine will make a nice match with that fish. In the right circumstances – say, on the sunny terrace of an ocean- or bay-side restaurant, with a light, fresh breeze gently cooling you – it can even become memorable in its simplicity.

.

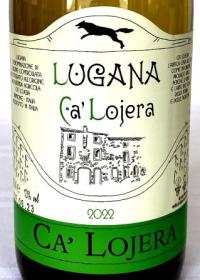

Raise the ante a little – make it crabmeat or lobster steeped in butter – and you want a bigger wine, with more character, one with a little minerality to play off against the sweetness of that shellfish. Then you’re going to need a Chablis, or a fine Lugana or Soave Classico, or even a good white from the Rhône – a wine that won’t be obliterated by the flavor of the lobster or crab. The key is only that the kids should play together peacefully, with no bully dominating the playground. Any moderately careful parent should be able to deal with that.

.

As I said, it’s not complex, and it certainly need not be expensive. We are lucky enough to be living at a moment when, whatever else may be wrong with the world, we have more good wine in greater variety available to us than at any previous time. Probably the only real problem confronting us is the sheer number of choices available – but as one who can remember the days when the finest, and one of the few, white wine choices on many restaurant lists was “Soavebolla” (for all practical purposes, one word), I can assure you that’s a great problem to have.

.

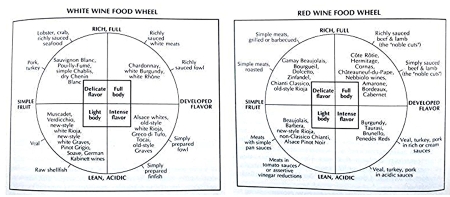

Should you want go a bit deeper into matching wine and food, or should you be perverse enough to enjoy complexity (I confess I do), here are two handy wine-and-food wheels I devised way back when for my book. I still like them, and I think you may find them handy.