The above is a title I once thought I would only ever use ironically. Back when I began as a wine journalist, when the Italian wine world was just beginning to awaken from its long slumber, an invitation to taste the produce of a regional cooperative was usually something I would firmly decline. Back then, most co-ops were turning out the least common denominator wine of their region – lots of it, designed to sell cheaply, to supply a supposed mass taste for nondescript plonk.

Well, the Italian wine world has transformed itself completely since then, and now co-ops are striving for quality production, and in most cases achieving it. Now, some of the most interesting tastings a wine maven can attend are those of cooperatives.

To understand how this came about, you need to know a little of the history of the co-op movement in Italy. For centuries, wine in Italy was a largely local affair, with growers – from the smallest sharecropper to the largest baronial estate – making wine mostly for personal and local consumption. A few of the larger growers bottled and commercialized their wine, but the market had nothing of its present-day dimensions. With a very few exceptions, Italian wine was very localized.

When Italy’s feudal sharecropping system, the mezzadria, finally ended (in the middle of the twentieth century!), small farmers fled the land for jobs in the cities, fields stood idle, and vineyards were neglected. A few producers with the resources bought up the land, consolidated the vineyards, and started commercializing their wines. The remaining smallholders, almost none of whom could afford to bottle their own wine, had little choice but to sell it to the big operations, usually – as you can imagine the market pressures – at a price more pleasing to the buyers than the sellers.

Enter the cooperatives. A few had been around for decades, mostly in the relatively few well-known northern appellations, where small growers had been able to merge their efforts and produce enough wine to be of interest to markets or distributors beyond their home region. Some of these are still active and very fine, especially in Alto Adige.

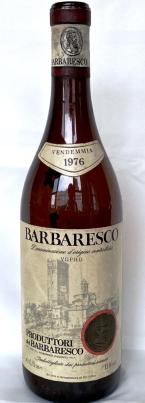

In Piedmont, one of the earliest and most successful cooperatives was Produttori del Barbaresco, which brought together small growers from all over the Barbaresco zone. It benefited from two key factors: a bevy of growers who worked many small but prized vineyards in prestigious parts of an important zone, and – maybe even more significant – enlightened leadership that from the beginning emphasized quality over quantity. Even now, in these days of superstar winemakers and much-hyped single-vineyard wines, the wines of the Produttori, whether basic Barbaresco, or Riserva, or any of the zone’s esteemed crus, stand in the front ranks of Barbaresco – which is to say, in the top echelon of Italian wine production.

.

.

Produttori del Barbaresco can be regarded as the pacesetter, but other co-ops in regions famous and regions scarcely known caught on quickly. Co-ops offer many advantages for their members, far from all of whom are specialized in growing vines or making wine. Many are old farming families who love living on their land and working it. They still practice mixed agriculture. They may have only a few hectares, but some of it will be in grapes, some in wheat or vegetables, some in olive trees. Co-ops help them make a reasonable living, and they may belong to several, one for their grapes, one for their olives, one perhaps for their cheeses. Nobody gets rich, but they can all make a living and continue to enjoy the kind of life their families have followed for who knows how long.

Nowadays you can find cooperatives all through Italy, in zones both famous and not-so. Over half of Italy’s wine production comes from co-ops: I think that there are over 500 of them. Some may be quite specialized, but usually they produce the whole range of their area’s wines, and usually these days at quite a respectable level of quality.

A good example can be found almost anywhere. Tuscany, for instance, which is in all respects a quirky region of hyper-individualists, now hosts several fine co-ops in some of its most important zones. One whose wines I’ve been drinking lately is one of the smallest: Castelli del Grevepesa, in the Chianti Classico region, comprises only 18 growers. Not surprisingly, with most of them located in Panzano, Lamole, and Greve, they work mostly with Sangiovese.

Following the typical cooperative pattern, their newly harvested grapes are transferred immediately to the co-op winery where they are fermented, aged, and bottled by the co-op team – a general manager, an agronomist, and an oenologist. From those grapes they make Chianti Classico, Chianti Classico Riserva, and Gran Selezione wines. As a further economic boost for the co-op members, Castelli di Grevepesa also produces grappa and extra-virgin olive oil.

.

.

Lately, I’ve been enjoying a lot of this co-op’s Clemente VII Chianti Classico Riserva 2018, a nicely balanced wine with lots of Sangiovese character and the kind of lively acidity that makes it a fine companion with all sorts of everyday lunches or dinners. And it has the added virtue of being quite inexpensive: It’s usually available for around $20, sometimes even less. To get a good reliable wine at that price, one I can enjoy with everything from hamburgers or steaks to, say, chicken pizzaiola: that makes me a very happy camper. You can see why I’m singing the praises of co-ops.

Read Full Post »