Diane and I have been drinking a lot of French red lately – mostly Burgundy and Rhône wines, very little Bordeaux. This is more than a little odd, for two reasons: one, that Burgundy is so appallingly expensive and two, that I used to love Bordeaux.

Bordeaux was what I learned wine on. In the US, way back then, wine was French, and the pinnacle of French wine for us tyros was Bordeaux. Bordeaux was affordable: Macy’s had a wine cellar then that sold 1966 Château Gloria and Château Brane Cantenac for $3 a bottle, with a 10% discount on a case. The great first growths were only a few more dollars a bottle. Sigh. We shall not see such days again.

Even more important, Bordeaux was comprehensible: Its classifications were easy to understand. And Bordeaux wines had the additional advantage of being abundant, and readily available on the American market. Bordeaux produced a lot of wine, especially compared to Burgundy, which besides being scarcer was also complicated – and already, in those days, expensive. So I learned Bordeaux, and I learned to love it. Cabernet Sauvignon was the grape for me.

.

Cabernet Sauvignon

.

But, as somebody or other in Shakespeare says, the whirligig of time brings in its revenges. Over many years, I found I was losing my taste for Cabernet. Was the grape changing? Was the way it was cultivated and/or vinified changing? Was my palate changing? The latter was probable, though I couldn’t rule out any of the former either.

Certainly, as my knowledge and appreciation of Nebbiolo deepened, it affected the way I experienced other varieties, most notably Pinot Noir, whose intricacies and nuances in many ways mirror those of Nebbiolo. So by way of Nebbiolo, I came to relish Pinot Noir, and to Nebbiolo I owe the few fine older Burgundies I am now enjoying. I wish I had more, but they were always expensive, and my budget always limited. I’m just grateful for the ones I have, and I choose carefully my opportunities to serve them.

.

.

Long-time friends are always a good excuse, so when two prime examples of such recently had a lull in their hectic schedules, Diane put together a French-ish dinner and I pulled out appropriate wines. To accompany the Simca-inspired eggplant quiche we started with, a 2011 Jaboulet Hermitage La Chapelle. And to match with an elegant chateaubriand and our very rich version of pommes duchesse, a 2001 Bonneau de Martray Corton Grand Cru.

.

.

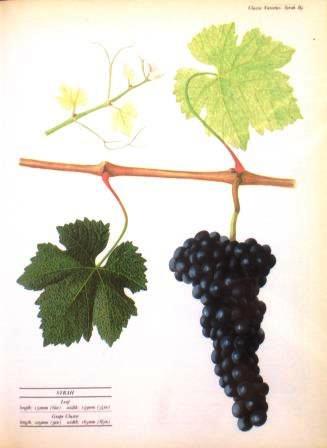

Those steep Hermitage vineyards bordering the northern Rhône tame the wildness of Syrah and turn it into a wine of lovely depth and impressive restraint. More than a decade of age had made that bottle’s suave character even better: unquestionably Syrah, but Syrah that had been to a top-flight finishing school. The quiche was smooth and sharp, lush and acidic. The Hermitage matched it note for note, as harmoniously as an operatic duet.

The Corton, from one of Burgundy’s most storied sites, and ten years older, showed every bit as elegant but slightly heftier, as if it were putting on weight with age. Nothing flabby, mind you: this was all muscle, smooth and sleek and just loving to play alongside that tender red beef. The two seemed made for each other, which – of course – is exactly what I had hoped for, and exactly the kind of thing that great Burgundy does best. This was a duet too, but baritones rather than tenors.

Much as I love pouring wines like this for friends, I can’t help feeling a twinge each time: I wish I had more. If I had known I was going to live this long, I would have bought and cellared my wines a lot more systematically. Wouldn’t I have? Sure I would: Diane can tell you what an organized, systematic person I am.